Žižek o Kosovu, Srbima i Albancima

/ 28.02.2008. u 02:48„Biću iskren: godinama sam zastupao albansku stranu. Ali ovo što se danas radi srpskoj manjini postaje nepodnošljivo. Postoje enklave u kojima živi najviše 15 osoba, staraca, dece... a štiti ih i po 200 vojnika KFOR-a. To je ludilo."

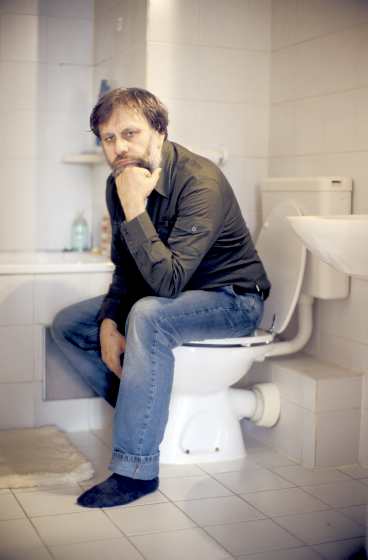

Slavoj Žižek (1949), slovenački politički filozof i kritičar kulture. Teri Iglton ga je opisao kao „ubedljivo najbrilijantnijeg" savremenog teoretičara poniklog u kontinentalnom delu Evrope. Žižekov rad je neverovatno ekscentričan. Karakterišu ga upečatljivi dijalektički obrti „zdravog razuma", sveprisutan smisao za humor, jedinstveni prezir moderne distinkcije između visoke i popularne kulture i preispitivanje primera uzetih iz najrazličitijih oblasti umetnosti i politike. Uprkos tome, Žižekov rad ima veoma ozbiljan filozofski sadržaj i ciljeve. Žižek osporava mnoge temeljne pretpostavke današnje levo-liberalne naučne zajednice, uključujući i uzdizanje Razlike ili Drugosti do krajnosti, tumačenje prosvetiteljstva kao totalitarnog, i preovlađujuću skepsu prema bilo kakvim idejama Boga ili Dobrog. Posebnu crtu Žižekovog rada čini njegovo izvanredno razmatranje nemačke idealističke filozofije (Kant, Šeling i Hegel). Žižek je takođe oživeo psihoanalitičku teoriju Žaka Lakana, interpretirajući ga kao mislioca koji ide korak dalje u odnosu na temeljnu modernističku posvećenost kartezijanskom subjektu.

Kasnih osamdesetih godina XX veka, Žižek piše novinske kolumne za list Mladina i učestvuje u izboru za člana slovenačkog Predsedništva. Prva knjiga objavljena na engleskom jeziku pod naslovom The Sublime Object of Ideology (Sublimni objekt ideologije)ugledala je svetlo 1989. godine, a od tada je objavio na desetke članaka, uredio mnoštvo zbornika i napisao preko dvadeset knjiga, delimično sledeći put Noama Čomskog koji je iz lingvističkih voda prešao i na političku/ideološku kritiku sa pozicija levice. Od 1997. godine Žižekovi radovi postaju sve eksplicitnije politički, osporavajući široko rasprostranjenu saglasnost da živimo u post-ideološkom ili post-političkom svetu i stajući u odbranu mogućnosti trajnih promena u globalizacijskom „novom svetskom poretku", kraju istorije ili ratu protiv terora. Jedna od poslednjih knjiga prevedenih na hrvatski jezik, pod naslovom Irak - posuđeni čajnik (Naklada Ljevak, 2005), bavi se ratom u Iraku. Trenuto uživa status planetarnog filozofskog superstara.

Mada je bio izričito kritičan prema srpskom nacionalizmu devedesetih, Žižek u poslednje vreme osuđuje nasilje nad kosovskim Srbima i zagovara kompromisno rešenje srpsko-albanskog pitanja. U intervjuu za italijanski dnevni list La Republica (prenosi nedeljnik NIN, 29. 11. 2007) tim povodom kaže:

Šta je sa srpsko-albanskim sukobom?

„Slažu se jedino po pitanju prostitucije. Biću iskren: godinama sam zastupao albansku stranu. Ali ovo što se danas radi srpskoj manjini postaje nepodnošljivo. Postoje enklave u kojima živi najviše 15 osoba, staraca, dece... a štiti ih i po 200 vojnika KFOR-a. To je ludilo".

Kako rešiti taj problem?

„Po mom mišljenju, samo podelom nadvoje. Vidite, humanost i multikulturalizam nalažu rešenja zasnovana na dijalogu i suživotu. To je, po meni, šarena laža. Istorija nam nudi mnogo primera - kada se dva naroda mrze, treba im dati mogućnost da se razdvoje, uz nadu da će vremenom uspeti da nađu zajednički jezik, približe se jedan drugom i ponovo početi da žive zajedno".

Znači, zidovi su nekad poželjni?

Znači, zidovi su nekad poželjni?

„Naravno".

Medijska dramaturgija nam je poslednje balkanske ratove predstavila kao ponovno buđenje varvarstva u srcu „civilizovane" Evrope...

„Ta je priča o mračnom i divljem Balkanu, naravno, kliše. Moje viđenje onoga što se dogodilo odgovara nekom najosnovnijem marksizmu: iza etničke ideologije skrivani su sukobi između državnih aparata i društvena neslaganja. Levičari tvrde da Milošević, iako negativac, nije izazvao raspad Titove države - raspad je, po njima, pokrenut secesijom Slovenije i Hrvatske. Ja, s druge strane, smatram da je upravo Milošević „ubio" Tita. Upravo je on dokrajčio već krhku ravnotežu u raspodeli moći među igračima i to na jedini mogući način - potpisavši ugovor sa đavolom, udruživši se sa nacionalistima".

Neki su u Srbiji davali i kontroverzne izjave po kojima je „diktator" ustvari doprineo liberalizaciji situacije. Vi ste se s tim izjavama složili. Pojasnite zašto.

„Tu je izjavu dao Aleksandar Tijanić i ja se s njom slažem. On je u stvari rekao da greše oni koji misle da je Miloševićev nacionalizam ovaplotio krute, cenzorske i represivne vrednosti. Naprotiv, on je Srbima rekao: sad možete da radite šta god hoćete! Sad možete da mrzite, kradete, silujete, napijate se, rešavate probleme oružjem. Pre desetak godina sam u Beogradu sreo srpske ultranacionaliste, Arkanove Tigrove na primer, i svi su mi potvrdili sledeće: u postmodernom, naizgled permisivnom, društvu oni su videli skup ograničavajućih pravila i zabrana: danas se više ništa ne može. Naprotiv, nacionalizam je ponudio slobodu delovanja. Adorno je taj mehanizam shvatio još tridesetih godina, analizirajući fašističku propagandu: Hitler, objašnjava on, nije nikakva očinska figura. Njegova je poruka lažni poziv na prestup: ispunjavaj moja naređenja i zauzvrat ćeš moći da radiš šta god ti je volja: da ubijaš, kradeš, siluješ..."

Blogovi autora

- Sveta Ceca (217)

- Almost All About Diva (285)

- Šmitova ideja suverene diktature u delima Zorana Đinđića (222)

- Uticaj stranačkih politika na Filozofski fakultet (81)

- Nek bude treći entitet (u Bosni)! (93)

- Dekonstrukcija Putina: intervju sa Mihailom Riklinom (45)

- Hoće li mačka pasti u provaliju? (31)

- Marksističke sablasti Fredrika Džejmsona (11)

- „My Name Is Wyatt Earp. It All Ends Now!“ (16)

- ProtoTractatus: Beleške o umetnosti (u Srbiji) (85)

- Свињски грип и драматизација болести (52)

- Oskar Vajld, nepostojani princ socijalizma (53)

- Novi napadi na Rome! (104)

- Stop rasističkoj politici gradskih vlasti! Podrška Romima! (159)

- Čudovišnost Hrista: Nužnost mrtvog pileta (43)

- Kako voditi ljubav sa srednjovekovnim pravoslavnim Slovenom? (55)

- Čemu još Gej Prajd? (91)

- Teze o gasnoj krizi (8)

- Kritika konzervativnog uma: poraz sociologa Antonića (263)

- Zašto volimo da mrzimo Paris Hilton? (38)

Najnovije VIP blogeri

- Dovidjenja, gospodine Bobicu!

angie01 - Klasicna tema- Beograd, popodne i gitare

jednarecfonmoi - Fragmenti stvarnosti u opštem prividu

Hansel - Horizontala, koja ne da vertikali da se vidi

angie01 - СРБИЈА ‒ ЗАЈЕДНИЧКА ДОБРОБИТ И КАЗНА

Predrag Brajovic - Lični izbori

njanja_de.manccini - Džez kao religija

Ivan Blagojevic - Diznijev svet

jinks - ovde je nigde dobro mesto ...

Đorđe Bobić - вабомамом спојке сунчане

Черевићан

Najnovije blogeri

- ŽUTA OSA (8/24)

horheakimov - DUB PUB: Milion kvadrata

docsumann - Dokon um đavolje igralište

zilikaka - НАЦРТ РЕЗОЛУЦИЈЕ О ГЕНОЦИДУ У СРЕБРЕНИЦИ

Filip Mladenović - DUB PUB: A Bright New Day Is Coming

docsumann - Srbija u EU i NATO do 2030...

Filip Mladenović - DUB PUB: Woman, Hey

docsumann - DUB PUB: No Love, No Home

docsumann - ŽUTA OSA (7/24)

horheakimov - Hronologija antipatriotizma...

Filip Mladenović

Arhiva

Kategorije aktivne u poslednjih 7 dana

- Eksperimenti u blogovanju (4)

- Muzika (3)

- Mediji (2)

- Moj grad (2)

- Zabava (2)

- Reč i slika (2)

- Hobi (2)

- In memoriam (1)

- Društvo (1)

- Kultura (1)